“The privilege of the writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in cases of rebellion or invasion the public safety may require it.”

A Writ of Habeas Corpus Explained

A writ of habeas corpus is a tool that the framers of the United States Constitution carried from England to enable any confined person to challenge the circumstances that led to their confinement. The confined person sues the person charged with keeping the confined person, which is usually the warden of a prison or of a detainment facility. Because a writ of habeas corpus is a lawsuit between two parties, it is governed by civil law. A person seeking relief through a writ of habeas corpus files a “petition for writ of habeas corpus” and may be referred to as the “petitioner.”

The American Legal Process

a typical criminal case

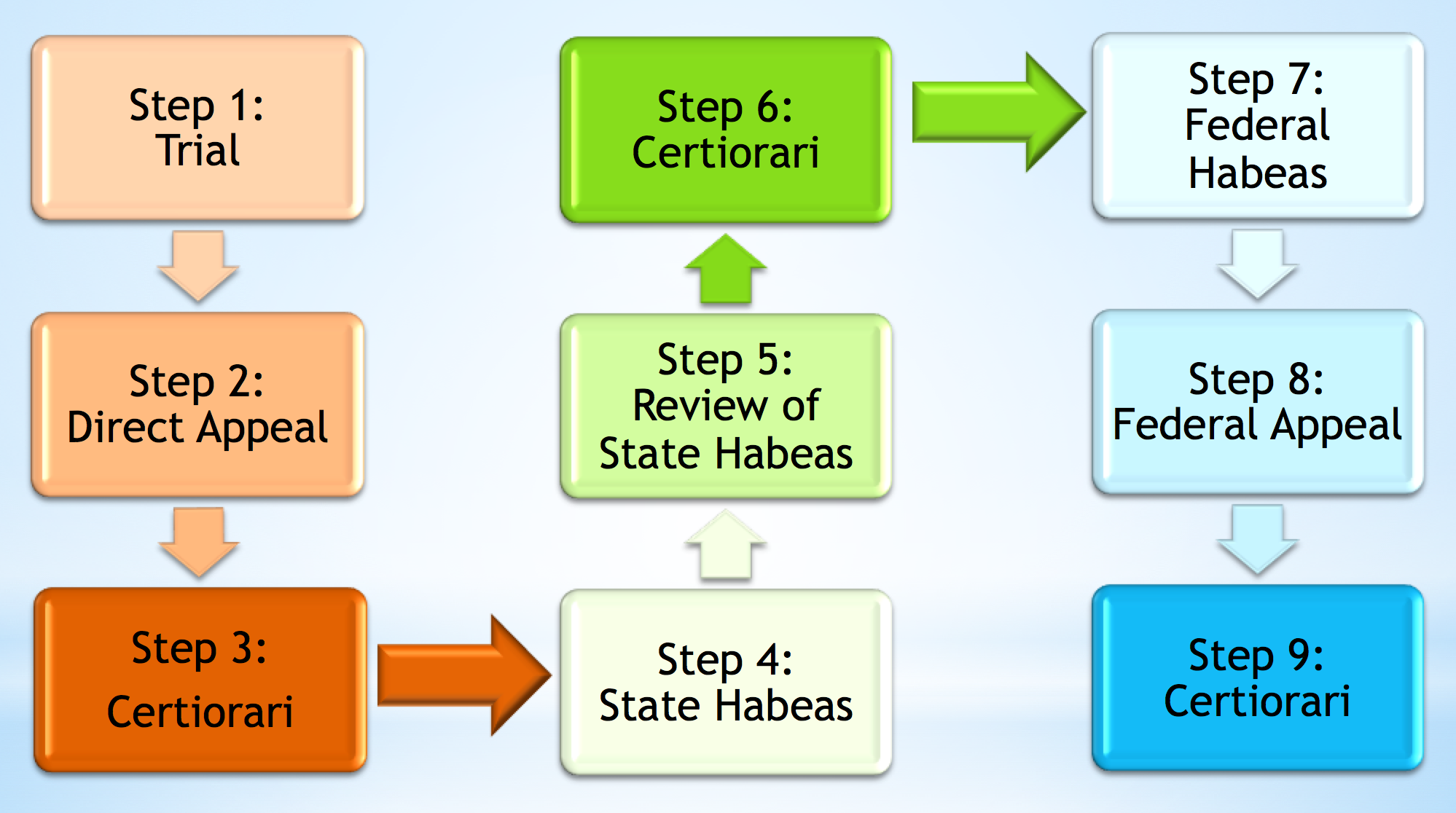

The diagram illustrates the way that a case moves through the trial, appellate, and habeas systems in the United States.

Typically, a case starts at the trial level. A trial may take place in state or federal court. This diagram follows a case that begins in state court. A trial includes both an actual trial and a guilty plea, because a plea happens in the trial court. All criminal defendants have the right to a lawyer during the trial or plea negotiation process. This does not mean that defendants have the right to choose their lawyer. If the court appoints a lawyer to the case because the defendant cannot afford a lawyer, that is the lawyer that the defendant gets. Usually, states provide defendants facing the death penalty with two lawyers.

“Direct Appeal” refers to something specific. In death penalty cases, most states provide a person convicted of murder and sentenced to death with an automatic appeal. In non-capital criminal cases, the defendant may appeal their case, but it is not automatic, meaning the defendant must file a notice of appeal with the trial court within a specific amount of time after the end of trial. Regardless of whether the appeal is automatic or not, all criminal defendants have a right to a lawyer during the appeal.

“Certiorari” refers to the “Petition for Writ of Certiorari” that a person must file if they want the United States Supreme Court to review their case. The United States Supreme Court is not obligated to review any case. It is entirely up to the Justices of the Supreme Court if they want to examine a case. If a person opts not to file a petition for certiorari, the petition for writ of certiorari is denied, or the Supreme Court grants certiorari but ultimately denies the petitioner relief, the petitioner’s case moves from the “Certiorari” box to “State Habeas.”

A Simple State Habeas

state habeas

“State Habeas” is the beginning of the habeas process. Remember that a writ of habeas corpus is a civil proceeding, not a criminal proceeding. This means a person filing a petition for writ of habeas corpus must follow the state’s rules for civil procedure to determine when the petition or subsequent motions are due. Because the habeas process begins at the conclusion of criminal proceedings, it is also known as “post-conviction.” Some states refer to the petition for a writ of habeas corpus as a “post-conviction petition” or just “habeas petition,” but at the end of the day, it all refers to the same type of lawsuit: suing the warden for unlawful confinement.

Only defendants whose trial happened in a state court have access to state habeas. If a defendant was convicted in a federal trial court, they cannot file a petition for writ of habeas corpus in the state courts. Remember that a writ of habeas corpus is a lawsuit against the warden who is confining the defendant. Thus, a person confined in a federal prison must file their lawsuit against the warden in a federal court. Only a person confined in a state prison may file a writ of habeas corpus in the state courts.

Every state is different. Some states require a defendant to file their writ of habeas corpus at the same time that they file their appeal immediately after trial; other states require the defendant to complete the initial appeals process. Every state is different in where it asks that a petition for writ of habeas corpus be filed. Because the rules and procedures differ for every state, it is very important to check the specific rules and procedures of the state where a person intends to file a writ of habeas corpus.

And the state systems are different than the federal system.

After the state trial court reviews a person’s initial habeas petition, the petitioner may usually appeal if they are denied relief. Many states have an intermediate court of criminal appeals or court of appeals. Sometimes all criminal defendants must first appeal to the intermediate court of appeals before appealing to the state supreme court. Sometimes only non-capital criminal defendants must apply to the intermediate court of appeals while capital defendants apply directly to the state supreme court. Regardless, there is no right to an appeal. The higher courts can decide not to hear a particular case.

If a court opts not to review a case or if a petitioner loses their case before the highest court in the state, the petitioner may apply for a writ of certiorari to the United States Supreme Court again. This time, the petitioner can only argue about the issues that they raised in their writ of habeas corpus.

Moving From State to Federal Habeas

The Anti-terrorism and effective death penalty act (AEDPA)

The United States Congress passed a law in 1996 that people seeking habeas relief in the federal court must file their petitions for writ of habeas corpus within 1 year of the conviction becoming final. A conviction is final when one of three things happen: (1) a person chooses not to file a petition for writ of certiorari after the direct appeal; (2) the person filed a petition for writ of certiorari but the Supreme Court declined to hear the case; or (3) the person filed a petition for writ of certiorari, the Supreme Court heard the case, but the Court upheld the conviction and sentence.

The federal courts do not require a person to seek state habeas and federal habeas relief simultaneously. Even though there is a one-year deadline to file the petition for writ of habeas corpus in federal court, the federal courts will pause to let a person complete state habeas proceedings.

However, the federal court does not pause to allow the United States Supreme Court to review a person’s petition for writ of certiorari after state habeas. State habeas is final after the highest court in the state denies the petitioner habeas relief.

This is one of the most confusing parts of habeas law. Lawyers get mixed up about state and federal habeas all the time. The courts do not give a person one year to file a writ of habeas corpus in federal court after the person has completed their state habeas. Instead, the federal court looks at how long it took the person to file their petition in state court and gives the person the remaining portion of the year to file a federal petition. For example, if a person took 3 months, or exactly 90 days, to file his writ of habeas corpus in state court, then they have 275 days (365 days minus 90 days) in which to file a writ of habeas corpus in federal court after the state habeas proceedings are complete.

Federal Habeas Process

federal habeas

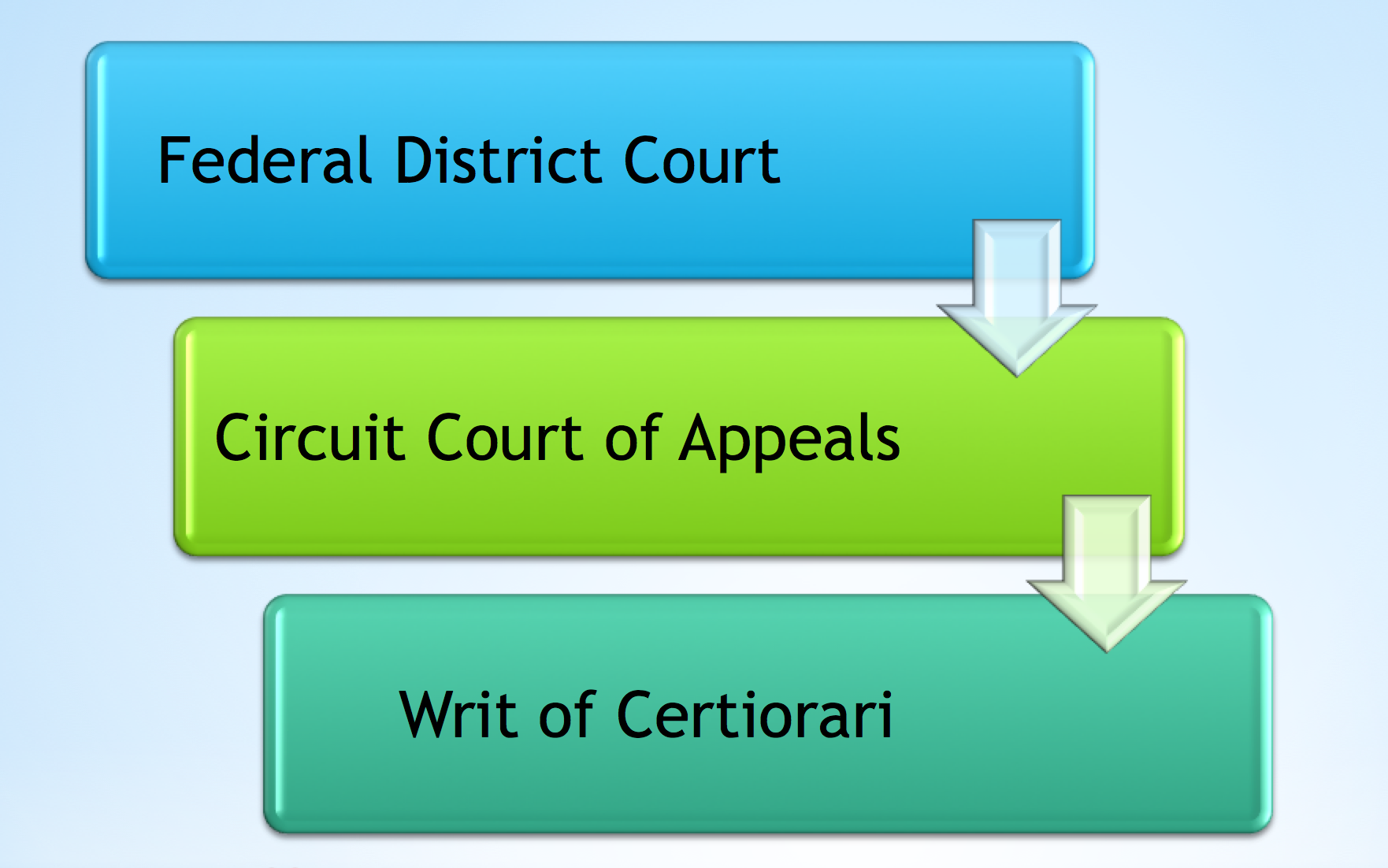

“Federal habeas” refers to the time after a person has filed a petition for writ of habeas corpus in the federal district court. Just like state habeas, federal habeas is a civil proceeding. And just like state habeas, federal habeas is a post-conviction process, meaning it is a process that begins after a person’s criminal conviction or detainment proceedings are complete. Federal habeas also goes by a few names such as “federal post-conviction,” “federal petition,” or “post-conviction petition.” Again, these names all refer to the process of suing a warden for unlawful confinement.

If a person was convicted in federal court, the process is simpler than the process for a person convicted in state court. The person convicted in federal court files a writ of habeas corpus under 28 USC Section 2255 in the court that held the trial or authorized the plea. If the trial court denies the 2255 petition, the person may file an appeal to the Circuit Court of Appeals that oversees the trial court. For example, a person convicted of murder in the Southern District of Florida would appeal to the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals. Below is a map of the federal appellate circuits:

Federal Appellate Circuits

Circuit Courts of Appeals have discretionary review, which means they can opt not to review a particular case.

If the appellate court opts not to take a case, or if the appellate court reviews a case but upholds the conviction or sentence, the person seeking habeas relief may file a petition for writ of certiorari to the United States Supreme Court again. Just as on direct appeal and with state habeas, the Supreme Court is not obligated to review a case.